By Brian T. McWilliams

Excerpt from the Sea Letter, Summer 2000 #58

By 1974 “A” men in the Clerks’ hall were sharing what little work there was. As little as 80 hours a month in January and February was about what was available. Bad times. I was sworn into the union in the middle of that slow time and as a brand new member ended up competing with men who had up to 40 years’ seniority on our “low man out” system of sharing what we have.

My first day in the hall as an “A” member I was loathe to go up to the window to get the first pick of precious few jobs. Because I had been a “B” man the previous month, I had worked very little and I started the next month as the first person out. This was based upon having the lowest previous month’s hours. I was ahead of many of those oldtimers, who were clearly not going to work. When my plug number was called I hesitated to go to the window,but one of the hungry old timers told me to get up to the window and take a job. “It’s your turn and we share what we have. When the going is tough at least nobody gets laid off and everyone takes home something to take care of his family with. When work is good we can all work as much as we want and that’s how we do it! Go to work.”

The waterfront was a great place to learn how to work and how to honor and respect labor. We were educated on our history and carried on a culture and lifestyle unique to dockworkers all over the world. It was a great breeding ground for internationalism and working class solidarity. I am fortunate to have seen it at its best and busiest and lament the lost opportunities to share that world with another generation.

I remember the Guitton buses that stopped at the halls to transport us to various terminals in the East Bay – as far out as Benecia. I learned how to figure out the highest pay rate while working on an ammunition loading operation down in the hatch of a ship in the stream on the 3am shift when the ship was on fire. I worked auto ships at Fort Mason and rail barges at Pier 43 and 52. I remember the vast amounts of alcohol that got drunk and the slow hard battle the union fought to change that culture.

There were so many more shipping lines then: American Mail, Grace Lines, Pacific Far East Line, American President Line, States Line, Matson and so many others. There was constant danger and inevitable accidents. Our comrades never seemed to get injured just a little bit. There were shipyard facilities at Piers 26 and 28,36 and 38,50, 70 and, of course, repair work ongoing wherever a ship was berthed.

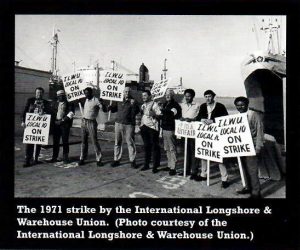

The 1971 strike lasted seven months from beginning to end, and I was on the night roving dock patrol for the duration of that strike. The best bonfire always seemed to be at the copra dock I recall the sound and sight of the belt line shifting cars. We had interactions with the Port Police. There were the green meters and the green meter stickers we bought at the hall so we workers could park all day. So many memories of a colorful and unique workforce. All this may be gone from the San Francisco waterfront forever.

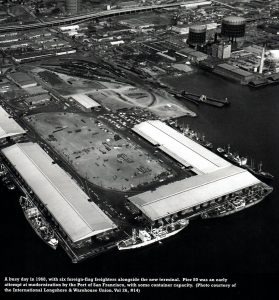

When I first started on the front in 1967, the Port, still managed by the State, had recently invested a large amount of capital in Pier 27, a new finger pier on the northern waterfront. Although this facility was new, it was not modern, and was filled Pacific Far East Line break-bulk cargo from the skin to the rafters. The state-of-the-art facilities were all taking shape in Oakland. A great deal of the work we enjoyed in San Francisco – coffee, cocoa, frozen meat and of course general merchandise – lent itself very easily to containerization. All this cargo joined the exodus to Oakland and other container ports on the West Coast.

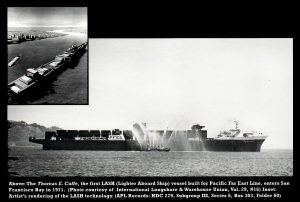

But in 1967, the prospect of a bright future for San Francisco’s waterfront was generally taken for granted .The few alarmists who shared a vision of the future as it actually came to pass were ignored. While San Francisco tried to accommodate the move toward intermodalism by building new facilities at Piers 80 and 96, Pier 80 only met the short-term needs of the industry. It was basically a traditional finger pier, on a grand scale, with a small central container yard. Pier 96, although more modern in design, provided no meaningful rail access and bet on the new and as-yet-unproven LASH [Lighter Aboard Ship] technology.

In the LASH system, ships carried covered barges which were lowered into the water at the destination port. h1 this way, cargo could be unloaded at ports without modern cargo handling gear, while the ship went on with her voyage.

The LASH concept was largely dependent upon the China trade taking off, with the anticipation of the normalization of trade relations with that huge country. The LASH system, with its lighter barges packed with cargo, would have worked well in China, given its expansive shallow draft river transportation network. But trade with China, due toboth political and economic forces, didn’t develop at that time and the LASH system was a bust.

The inability or reluctance of the railroads to serve the San Francisco peninsula in a timely or economically viable way was big factor in the failure of the Port to retain maritime clients over the years. I believe there was a conscious effort by Southern Pacific to milk the rail markets in Northern California in order to fund huge capital investment in the southern crossing out of Los Angeles/Long Beach to the rail heads of the heartland.

Even though the railroads were given vast land holdings in exchange for providing service to our communities, any marginal and unprofitable lines were sold off without consideration for the general public welfare. Northern California and particularly San Francisco paid the price for infrastructure improvements in the areas most lucrative for the railroads. Even so, some degree of fault for the cargo flight does need to be laid at the feet of the planners, policy makers and industry moguls involved in infrastructure and Port decision-making over the years. The tunnel reconfiguration project, designed to provide double stack rail service to San Francisco’s marine terminals, was stalled for lack of the will to make it happen. This is a case of not having the confidence necessary to believe in a vision for the future of maritime industrial jobs. This is the kind of thinking that has led to the demise of a vibrant and vital organ of a once prominent seaport of the west.

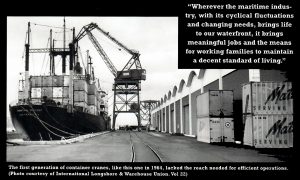

American President lines is another example of our lack of faith in our own abili ties as a port. APL wanted to stay at Pier 80, but a number of issues were never resolved, speeding their departure for Oakland and other ports. One issue was the container cranes which could not reach far enough offshore to work the outboard boxes on APL’s new ships in the early 1970s. A ship would literally have to be turned around to fully load and discharge. Needless to say we had to find this out the hard way. APL might not have chosen to stay in San Francisco forever in any event, but we didn’t help.

The Port’s lack of reinvestment in infrastructure during the State period, and our own lack of faith in ourselves as port operators, has continued to cost us in maritime employment opportunities. Retaining or attracting maritime jobs has not been done in an aggressive and strategic way. The result has been that San Francisco has been a dead port for some considerable time. Ifwe don’t believe in our own ability to bring meaningful and good paying industrial jobs to our community, with all of the side benefits of those jobs, then we will never achieve it. It is all too easy to be diverted by managing what arguably is the most precious real estate in the country. We must not make the decision to exclude maritime.

The port is now striving to revitalize its maritime business through much hard work by a committed site, and then ultimately work to push the industry out. The waterfront also is under pressure exerted by people and communities who are not concerned with the port and port operations as a vital economic engine for the city.

I believe that there must be tolerance by both the new communities and waterfront industry, so that we can reach a balance where each group can survive alongside the other with some degree of harmony. Unfortunately, we see a trend toward an all-or-nothing scenario. There is little understanding that once a maritime facility is lost to commercial or industrial use, it is lost forever as a maritime resource. The impact of this loss on future jobs and economic opportunity is elusive. When port facilities lay idle for long periods, awaiting the development of viable marine/industrial uses, we see an understandable loss of public support for maintaining the potential of this great resource. Wherever the maritime industry, with its cyclical fluctuations and changing needs, brings life to our water front, it brings meaningful jobs and the means for working families to maintain a decent standard of living.

I was innocently happy when I first started working on the docks at a basic rate of about $34.00 a day. I had little idea at that time of the larger social implications of the waterfront and its union on the fabric of this city. I could not have imagined the coming years on the waterfront, and how that culture and that union would impact my life and that of my family. I only hope that other kids coming along will find something of the same sense of community and useful work that have been so important to me.

BIO

A San Francisco native, Brian T. Mc Williams began his career in 1967 as a merchant seaman and member of the Sailors Union of the Pacific. He is now president of the International Longshore & Warehouse Union, a position lie has held since 1994. Mr. McWilliams was appointed to the San Francisco Port Commission in 1998.