By Carl Nolte

Excerpt from the Sea Letter, Summer 2000, # 58

In Baghdad by the Bay, the book that defined his vision of San Francisco, Herb Caen wrote of the waterfront around midnight, fifty years ago: “Along the Embarcadero great ships sleep at the end of their lines, moving ever so slightly, as if in a dream.”

To Marvin Wong, a native San Franciscan who is now a volunteer on the submarine USS Pampanito it WAS a dream.

He remembers wandering on the waterfront as a boy, seeing the little tractors that hauled carts full of mail up the Embarcadero, watching the big white liners Lurline and Matso11ia sail off to the south seas, and the big relief map of California they had, at the Ferry Building. “Those were wonderful days,” he says. “I can’t even explain it to my children. They don’t understand. It’s a different time zone.”

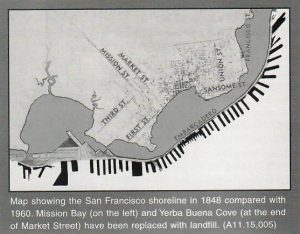

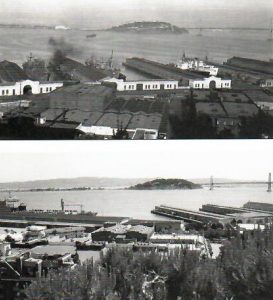

The waterfront that Caen wrote about and Wong remembers is gone. It’s a new world now. The working waterfront has turned into the Embarcadero parkway; ships from around the world have been replaced by tourists from around the world; the waterfront warehouses have turned into Multimedia Gulch; Pacific Bell Park has replaced a working pier; China Basin has become McCovey Cove; the old Army-Navy YMCA is now the fancy Harbor Court Hotel; the sixty-six miles of the State Belt Railroad has been replaced by two MUNI streetcar lines; and Pier 39 has morphed into a sort of Disneyland North. By day the Sailors’ Union of the Pacific building on Rincon Hill is a hiring hall for sailors, by night it’s Maritime Hall, the concert venue for hip-hop, reggae and other looney tunes.

Even the Embarcadero sidewalk, where seaman and longshoremen fought the ship owners for control of the waterfront, has been renamed. Now it’s Herb Caen Way.

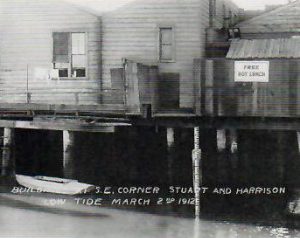

Of all the places in San Francisco that have changed, the waterfront has changed the most.

One has only to walk along the waterfront to see. From the nearly buried railroad tracks near Fisherman’s Wharf to the tugboats rolling gently in the Bay swells at Pier 15, to the Java House a t Pier 46 in the shadow of Pacific Bell Park, the past is right there beside the amazing present, a mixture like a kaleidoscope, little bits of shifting light and color, different eras changing in front of your eyes.

“It was a hell of a place to be,” says Tommy Tomlinson, who remembers the San Francisco waterfront in World War II, perhaps the busiest time in its long life. “It was 1943 and I was back from the South Pacific. I was a country boy from Montana and here was San Francisco.

“There were all these all-night joints and dives. It was kind of an open town, it was looser than it is now, and safer.”

“There was quite a contrast between the waterfront and the rest of the city. Uptown it was very staid. All the dames wore gloves and the men wore vests. These people looked down on the waterfront; they thought the seamen were all a bunch of lower class Commie bums. There was a real class difference.”

Some years later Tomlinson went to sea and worked his way up from a sailor’s berth to master with the military Sea Lift Command. He came up ‘through the hawse pipe’ as they used to say. And he sailed out of San Francisco Bay.

The waterfront, he says, was “changing rapidly” even then, back in very recently: as late as the 1970s, ships from the Norwegian WestfalLarsen line and the American flag Prudential Grace line ran from San Francisco around South America and back. The Mariposa and Monterey sailed from Pier 35 for Hawaii, the sound of their whistles echoing off the Telegraph Hill apartment houses as the big passenger ships backed out into the bay.

The President Cleveland and the President Wilson went to Japan and Hong Kong, which then seemed farther away than they do now. Those ships are gone, and the times with them.” The containers wiped out the most interesting part of the waterfront,” says Tomlinson. “I loved the old-time waterfront, but by the same token you can’t stop progress. It was great for its time and place, but there is a time and place for everything in this world.” There was even a time and place for the Embarcadero Freeway, built in the middle ‘50s as a road to a future that never happened.

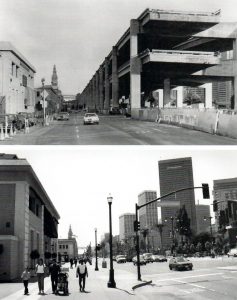

As the years went on into the 1980s, the Embarcadero hit bottom. The ships that had called in San Francisco were gone to the scrap yard or to the booming port of Oakland, the piers were collapsing, and the freeway, ugly, grim and gray, cut off the water from the city.

The earthquake of October 17, 1989, changed everything. The quake bent the flagpole on the Ferry Building, stopped the clock at 5:04 and wrecked the freeway beyond repair.

The old freeway had to go, and now all the old plans for the Embarcadero could come to life again. In a few years, there was a new waterfront.

Starting at Fisherman’s Wharf, the old Embarcadero got a new look, with palm trees and a streetcar line –“The Toonerville Trolley,” some waterfront people call it.

Sweeping south from the wharf, one can see the difference. At the Underwater World at Pier 39, for example, a whole family can view the fish for a mere $29.95. In 1930, an ordinary seaman sailing out of that pier made $30.00 a month.

The pier shed at Pier 27 houses a fleet of limos, motorized cable cars and horses-and-buggies for tourists. On the pier face the big, gray Maritime Administration ship Cape Henry is tied up, the only active dcepwater ship on the northern waterfront.

Pier 15 is the home of Bay & Delta Maritime and there is usually an assortment of tugs in port, ready to go.

There are also the pilot boats at Pier 9. Pier 7, once the home port for the famous coastwise steamers Yale and Harvard, is now a fishing pier.

The ferryboat Santa Rosa, painted the colors of the long-vanished Southern Pacific-Golden Gate ferries, rides her mooring lines a t Pier 5. The boat, which will be seventy-three this year, is now a floating office.

At Pier 3, too, one can still see the special slips built for the palatial river steamers Delta King and Delta Queen, which sailed every night at 6:30 for Sacramento. The Delta King and Queen still live, but the port they left behind is much different.

The centerpiece of the waterfront, the crown jewel, is the Ferry Building, once again serving its original function. Next year it will get a total overhaul and a new life.

The plaza where Market Street meets the Embarcadero is also being overhauled and has been renamed for Harry Bridges. Once, the name of Bridges could start a riot on the waterfront: he was loved, hated, reviled and respected. For years, the United States government tried to have him deported on grounds he was a Communist. Now, his name will grace the center of the waterfront. Times have changed.

On baseball days, big crowds walk along the southern Embarcadero, past the pier where the fireboats Phoenix and Guardian are berthed, under the soaring Bay Bridge, past Red’s Java House (where a beer and a cheeseburger is still the breakfast of choice), past the Boondocks, still an authentic dive.

A few of these passersby might pause to glance at what’s left of Pier 30-32, where an attempt to break a waterfront strike in 1934 set off a riot ending in the deaths of two men and a general strike. It was a watershed event, but the shouting and the bitterness have faded away now.

Beyond that is an upscale restaurant, and the definitely downscale Java House, where owner Philip Papadopoulos remembers the days, not long ago, when the neighborhood was nothing but “a wilderness of abandoned warehouses and rusty railroad tracks.”

Now there is Pacific Bell Park (now AT & T), on Channel Creek, once the home of hay scows and banana boats. South of that, across the Lefty O’Doul Bridge, is what’s left of San Francisco’s working waterfront: the San Francisco Drydock, Inc., more military sea lift ships, and at the foot of what was once called Army Street, a few cargo piers.

Bob Featherer, who sailed from Pier 35 in San Francisco as third engineer on the Matson liner Monterey, misses the old waterfront. “Oh yeah,” he says, “I met my wife the Monterey. I miss those days, but they aren’t coming back. I don’t see the port of San Francisco coming back.”

Featherer sailed for years; his last berth was a chief engineer on the container ship President Kennedy (at 962 feet long and 77,000 deadweight tons, the largest merchant ship to fly the American flag).The Kenned y’s home port now: Oakland.

San Francisco’s new waterfront “is interesting” says Captain Patrick Moloney, executive director of the State Pilot Commission, the oldest agency of California’s government. “It would be nice if there were all kinds of ships tied up here, but objectively, that’s not gonna be,” he says.”

It’s regrettable that it’s gone,” says Captain Tomlinson. “But there it is. I have to tell you, I really enjoy the way it looks now. Frankly,” he says, “I like the look of it.”

“I like it very much,” says John Bonjean, beverage manager at Sinbad’s, a waterfront bar with a knockout view. “Look at what’s happened in the last four years,” he says. “The ballpark, the plaza, the streetcars. It’s wonderful.”

The feel of the sea, he says, is still there. Sometimes, at night, as they are closing out the bar receipts, the crew looks up and sees the big ships moving in the night, coming under the Bay Bridge, blotting out the light. It can take your breath away. “It’s amazing,” he says.

The old San Francisco waterfront “is not coming back,” he says. “Forget it.”

Bonjean looks at the visitor who spent years watching the salt water. “It’s not the San Francisco we knew,” he said. “But the change had to happen.”

Click Image for Larger Picture