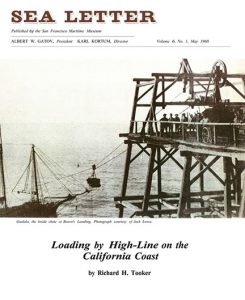

By Richard H. Tooker

Excerpt from the Sea Letter, 1968, Vol. 6 No. 1

It is no coincidence that the cable car and the wire chute date from the same decade, the 1870s, for it was after the Civil War that wire rope of practical quality became readily available in California. The cable car eased the problem of providing street-railway service up San Francisco’s hills, while the wire chute eased the problem of operating a sea- port on an open, cliff-lined shore.

California’s coast was and still is notoriously poor in harbors, at least by the standards of the Atlantic States. Even worse is the fact that the coast lies under a prevailing wind and swell. Also, many locations of early economic importance, blocked by the Coast Range from easy access to the interior, had a sea front of high bluff and open bay where a wharf simply could not be held for longer than a summer at a time, at best.

At these last-mentioned locations, recourse was had at an early date to the use of glorified playground slides with adjustable aprons at the outer end. These were the famous slide chutes. They are usually thought of in connection with the north coast of the state, but were also found south of San Francisco as well. Although they were gradually- superseded by the wires (as the high-lines were always called), the last slide chute did not disappear until well after 1900.

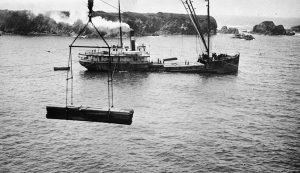

When the ready availability of suitable wire rope made high-lines practicable, the question was: Could one be set up in some way at ports where the water was too shallow near shore for a schooner to come close enough to be reached by a slide? There would also be the economic advantage of loading by the sling-load, plus the fact that this style of loading would also cut down the time a vessel had to stay in port at locations where sudden changes in weather could be very troublesome, if not disastrous.

A certain amount of experimenting took place at different locations, but the first widely adopted, practical solution appears to have been worked out by two skilled mechanics of Canadian ancestry who had settled in the Gualala area. They were Will St. Ores and his brother George. Although some of their installations were sup- plied with power from a small donkey engine, the classic St. Ores wire, as it was used principally in the area be- tween Pt. Arena and the Russian River, was operated without the use of an engine, and it is this form of the wire chute that will now be described.

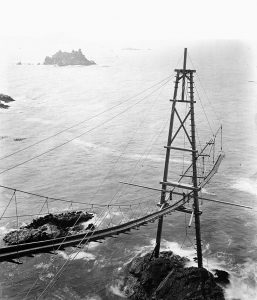

The location having been chosen from the point of view of the configuration of the shoreline both above and under water, the exact site was picked out at the edge of the bluff. A wide, shallow trench was dug in the ground, run-ning straight back from the edge of the bluff, and a substantial platform was set in place over the trench.

A framework was erected over the platform strong enough to handle the necessary weight and stress. Mounted in the framework and high enough to clear all traffic below it, was a shaft with two drums riding on it. Also mounted in the frame was a sequence of sheaves over which a wire rope could be run from the deadman behind the platform to pass through a wooden block banging over the outer (sea) end of the platform. Two vertical uprights in the framework made a slide-frame in which the block could move up and down. Handled by a double-block pulley rig, the height of the block (and thus of the wire) over the platform at the front could be adjusted as desired.

The floor was actually in two parts: the platform proper, and the heavy U-shaped section in which it was mounted by means of a heavy hinge at the rear, so that a weight resting on the platform would tip it down. Underneath, a counterweight was rigged so that when there was no weight on the platform the floor would be held level. A heavy handle-beam secured to the platform had a rope led from it which could be taken around a cleat on the forward upright where the chute operator stood. In this way the platform could be held level, even with a weight on it, till the rope was cast off.

The two drums on the overhead shaft were of different sizes. The haul-back line for the traveling sling-carrier that ran on the wire, was taken around the larger drum. Around the smaller drum was wound another line that ran to a counterweight hung from a wire running down the bluff toward the beach. The idea was that the descent of the counterweight would turn the drum-shaft, and bring the empty traveler back from the ship, while the loaded traveler would be heavy enough to drop down the wire to the ship and pull the counterweight back up. The size of the drums was adjusted for the distances involved; typically, the ratio was two to one.

The wires began to disappear after the First World War, when the loss of the market for redwood ties, to creosoted fir ties, ended the need for the small landings. Besides, supplies could now be brought in easily by motor truck. Mendocino and Caspar, however, with no rail connections inland, continued to depend on the wire and the steam schooner for getting their lumber out.

The depression shut down the wires, but as conditions improved there was intermittent operation at Caspar until the sailors’ strike of 1936-37. The resulting increase in wages drove ship operating costs up, but the real backlash came from the institution of the union hiring hall on a strictly rotational basis. The operators could no longer be sure of getting the same crew trip after trip, nor have any assurance that the new men they got from the hiring hall would know how to handle moorings and set up and work under a wire. This loss of efficiency drove costs up even more.

Mendocino’s mill had been left shut down, since it was no longer needed now that trucks were capable of hauling logs from the Big River Woods to Fort Bragg; while at Caspar, the cost margin was now definitely in favor of trucking the lumber below.

So the end came in 1938, although the last chute was not actually dismantled until at the end of the Second World War, when it had become obvious that shipping lumber by water was no longer necessary, let alone economical.

Today, only a few signs are left of the old landings, such as the timber foundation for part of the chute house on the point at Mendocino, and some scattered pieces of back-action chute frames at locations on private property not visible from the Coast Highway.

By Carl Nolte

Update from the The Sea Letter Magazine reprint, Spring 2004 # 70

When the above high-line story was reprinted nearly a half century later, the supplemental article below, authored by Carl Nolte, was featured as a sidebar story.

California has changed a lot in the past century but nothing has changed as much as the Redwood Coast, once the realm of sailing lumber schooners like the C.A. Thayer and steam lumber schooners like the Wapama. The coast was once lined with sawmills which cut the redwood and fir timber from the vast forests into lumber for the cities of California. The Victorian houses that are the pride of San Francisco, Oakland, Alameda, Berkeley and other cities came from these mills and these forests. San Francisco was rebuilt after the 1906 earthquake and fire with lumber from these mills, carried to San Francisco on small coastwise lumber schooners.

But the timber industry and the sawmills are pretty much only a memory on the Sonoma and Mendocino coasts. The small towns — places like Little River, and Albion, Gualala and Fort Bragg — have survived. But instead of sawmills, the beautiful and rugged coast is lined with small inns, and vacation homes. Instead of lumber, the principal industry is tourism.

One particularly handsome stretch of the Sonoma coast has been transformed into the famous Sea Ranch development. And just north of Gualala, in Mendocino county a handsome resort has risen, with a main house built like a Russian Orthodox cathedral, with onion domes and stained glass. The food is gourmet and famous. Travelers can rent comfortable wooden cabins with views of the ocean and the rocky little coves that once were lumber ports. The place is named St. Orres, after the two Canadian brothers who developed the wire loading devices used up and down the coast.

But the lumber ports and the ships that called there are nearly forgotten. Only here and there, if one looks very carefully, bits and pieces of the old landings can be found, like artifacts of a vanished age.

The Sea Ranch was once a high-line site

Tourism replaced many high-lines